Science, Evolution, and the Baha'i Faith in Bryan Donaldson's 'On the Originality of Species: The Convergence of Evolutionary Science and Baha'i Teachings'

Book Review: Reflections on Scientific Advancements, Baha'i Belief & Intellectual Diversity

“The human spirit, which distinguishes man from the animal, is the rational soul, and these two terms—the human spirit and the rational soul—designate one and the same thing. This spirit, which in the terminology of the philosophers is called the rational soul, encompasses all things and as far as human capacity permits, discovers their realities and becomes aware of the properties and effects, the characteristics and conditions of earthly things. But the human spirit, unless it be assisted by the spirit of faith, cannot become acquainted with the divine mysteries and the heavenly realities. It is like a mirror which, although clear, bright, and polished, is still in need of light.” - ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Some Answered Questions #55

A New Contribution on the Baha'i Teachings and Evolutionary Science

'On the Originality of Species: The Convergence of Evolutionary Science and Baha'i Teachings' is a recently published (late 2023) work by the Baha’i author, Bryan Donaldson, that attempts to reconsider ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's statements on evolution in light of some interesting prospective developments in evolutionary theory and modern genomics, developments that may necessitate re-envisioning evolutionary thought. It is the first book-length treatment on the subject of evolution and Baha’i belief in the last 15 years, and for this it deserves credit as a contribution sparking further interest in this somewhat languishing topic of study.

This work is also notable for being the first Baha’i work to focus on addressing specific scientific research that accords with taking at face value ʻAbdu'l-Bahá’s statements on evolution, statements that, from a certain glance, appear to conflict with conclusions in modern evolutionary science. Donaldson attempts to take the overt meaning of these statements to their logical conclusion through direct recourse to emerging scientific evidence, evidence that he suggests may amount to an alternative scientific model that explain humanity’s emergence through an independent natural evolutionary origin.

Whether you find the arguments ultimately convincing or not, this book treads new grounds on a few fronts: in light of its consolidation of Baha’i statements on the subject, reflections on the updated translations of ‘Some Answered Questions’, and through the bold step of attempting to explore correspondence of applying Baha’i thought through select scientific advancements in the field. It offers a useful summary of all the available direct statements on evolution in Baha’i Scripture, and for that alone, it is worth a read. Similarly, readers wanting to find an enjoyable read that introduces scientific topics in evolution will find Donaldson capable of sparking interest in important topics in the field.

In the interest of providing conclusions up front, my key takeaways are the following:

The book is eminently useful in its review of this topic from a Baha’i perspective and the resources it centralizes into a single place.

Donaldson is an able writer, the book is an enjoyable read and is accessibly written.

It takes great courage to pursue a heterodox approach to scientific evidence, and I commend the author for his willingness to do this. Whatever its flaws, this isn’t ‘crackpot’ thinking, it is not Creationism and is genuine in its engagement with scientific evidence. Scientists and interested readers will benefit from a willingness to ask ‘what if?’ and to entertain alternative perspectives. Indeed, this is necessary for scientific development.

I am broadly sympathetic to its goals, although I am not personally convinced that the proposed model will consolidate into a novel synthesis of evolutionary science. However, I do not believe that any single book is capable of demonstrating such a development, or at least this is not such a book, as I will explore more below. The presentation is nonetheless worth contemplating even if it only serves to affirm that the route it follows is presently a lost cause.

What follows is something of a book review; in this my aim is not to systematically evaluate the validity of the research it presents. Rather it is a reflection on belief, scientific models, and the value of contributions such as this book to the evolving discourse on humanity’s self-knowledge in relation to scientific evidence of our origins. As a reminder, the views expressed in the book and in review of it are merely the impressions of the authors. Buckle up, this is a lengthy one!

Evolution and Baha’i Belief

In the modern era, evolutionary science has become one of the stark dividing lines in the ‘battles’ over the conclusions of the Enlightenment, scientific thought, and the intellectual and spiritual heritage of religion and antiquity. For some, it is the cornerstone of the very falsification of religion itself and the crowning gem of materialistic philosophy. For others it is a rallying cry to the banners of an insistent religious piety and entrenched fundamentalism. Much like other features of modernity, this impels some members of the world’s major traditional religions (certain wings of Christianity, Islam) to retreat into a kind of traditionalism and pining for the premodern, an overriding desire to restore the purity of their movements as they originally were founded. Ironically, this effort to reclaim the ‘original truth’ of those traditions is decidedly modern.

For Baha’is, it is none of these things, as we will explore.

My first real run-in with young earth creationism was when I was 10 years old. For fifth grade, my parents sent me to a private 'church school’ organized by the local Seventh Day Adventist community in our remote community in NW Alaska. Not because I or my family were Christian (I was raised as a Baha'i), but because it was more or less the only option left for my schooling. I lived in a small, remote community where educational opportunities were slim and I had already burned through the two other options for schooling (the local public elementary school that I had dropped out of the year prior and home-schooling) at the time. As long as I was getting a good "private school" education, and they were respectful that I wasn't Christian, how bad could it really be?

That year of school turned out to be one of the most absurd experiences of my life, but one for which I am surprisingly grateful. The whole year was a complete mess, but very memorable. At one point, myself and 3 classmates got lost on the open tundra for over 2 hours in a freak blizzard because the school’s idea of ‘recess’ was sending 30 kids out into the barren tundra with shovels for an hour a day. We were blamed, of course. Students were punished for any perceived misbehavior by being forced to copy line-by-line from pages of the dictionary. Certain offenses were known as a one-, two-, three-, or 'ten-pager', respectively. I attribute my wildly precocious vocabulary to the amount of dictionary pages I had to copy that year. Naturally, we devoted an inordinate amount of time throughout the week to bible study where, even as a 10-year-old, I would ask probing questions about passages that did not accord with my understanding of Baha’i beliefs, or that simply seemed nonsensical.

The positive side effect was that I found such bible study sessions (10:00 am daily) actually quite fascinating, despite not being Christian. I credit my knowledge and interest in the bible to those classes, though they likely had the opposite effect intended. Already at that age, I'd had a strong awareness of my Baha'i identity, the history of our Faith, and the central principles. I knew that Jesus' teachings formed a bedrock of the Faith, but also discerned that the Bible was a complicated collection of conflicting narratives that came with a variety of interpretations (and misinterpretations), some of which I could clearly tell didn't align with personal sensibilities or from a Baha'i perspective. One, among many, was the idea that the Earth was less than 6,000 years old, which just so happened to be a strong point of emphasis during many study sessions at this church school. I had taken a strong inclination to science & history in those years and found these discussions quite laughable. I vividly remember one day, returning home, absolutely flabbergasted that we were discussing, in school, that if dinosaurs were real Jesus must have walked with them. Or that the reason they died out must have been because they didn't make it onto Noah's Ark.

Baha’i Beliefs on Evolution

It wasn’t until I was a teenager that I truly began to explore the specific Baha’i Writings on evolutionary science. The most important principles relevant to the discussion are the core principles of progressive revelation and the harmony of science of religion. These are ideas that all Baha’is are familiar with but, as they are truly bedrock principles, the exact way they trace out for individuals’ interpretations of scientific evidence on subjects like evolution will naturally vary, as we will see.

Let’s get one thing out of the way quickly: Is this book advocating for an alternative to evolution?

No. It is perhaps more akin to how Modern Synthesis is a significant adaptation and extension to Darwin’s original model, or Extended Evolutionary Synthesis is an adaptation to Modern Synthesis. The proposal Donaldson explores would be a marked shift in the scientific consensus, no doubt, and more far-reaching in implications than ones seen so far due to the weight of evidence in favor of the consensus. But it is not entirely inconceivable, even if the ground remains shakey. Hence, this book is definitively not evolution vs contraevolution, or science vs pseudoscience. Rather it is the current model of evolution vs a proposed extension, revision, or revolution of it. It leans closer to revolution in the size of its claims, and for this it unavoidably falters, for one can only go so far in demonstrating such grand new syntheses within such a confined format.

What exactly is he proposing?

One of the most prevalent allegories for evolutionary origin relates to evolutions most fundamental principle: that life on earth all emerged from a common point (universal common ancestry) and thereafter diverged into varying branches continuing and diverging into own subsidiary limbs, twigs, etc. This produces an image of a standard tree and forms the basis of ‘phylogeny’ and is largely responsible for sensibility and explanatory power of evolution as a framework. The vision that this book proposes is one where instead of a single ‘tree of life’ with the universal common ancestor of all life at it’s root, there are instead multiple ‘trees’ with intersecting roots systems and overlapping branches, creating an altogether more complex picture of evolutionary development. It seeks to justify this vision via a set of mechanisms that explain phenomena such genetic similarity, that traditionally undergirds analysis of common ancestry, by recourse to alternatives that may explain the same observations (these being horizontal gene transfer, convergent evolution and parallel evolution, constrained evolutionary pathways emphasizing evolutionary modularity and repeatable origins, and others). This provides a model to explain the varying origins of species while also explaining ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s statements, taken literally, suggesting man has always been man. In this vision not only would human beings be able to trace their own unique lineage to a common matrix of organic life, but so would other groups of species.

So the Baha’i Faith believes in evolution?

When it comes to evolution, as Donaldson emphasizes well in his introduction, Baha’is do believe: (1) that humans have gradually evolved into their present form, (2) that cosmological and mythic origin narratives (a la Adam and Eve) from past religions are not to be viewed literally but allegorically/spiritually, (3) that human beings are subject to dictates of material nature including forces like natural selection, (4) that this occurs on the scale of millions and billions of years. It’s settled then, right?

Well, not exactly.

The crux of the distinction of Baha’i belief from the present state of science is this: supporting as it does, the scientific endeavor of investigating reality and coming to an evermore clarified picture of natural processes and material reality, Baha’i thought contends that although human beings share, to some degree, the natural and evolutionary processes that determine animal species and the nature of other organic beings, we remain definitionally and distinctly human in our powers and capabilities—in our essence—and are not to be viewed merely as animals.

That this is an evident fact is, I think, borne out from the totality of Baha’i Writings on human nature and spiritual reality irrespective of whether we had any of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá’s statements on human origin and His reflections on the materialist philosophy of evolutionary science of His time (the turn of the 20th century, during which He wrote, spoke, and toured the West and expounded Baha’i principles on this subject). This is an important point to clarify because it has a bearing on the ultimate conclusions of the Baha’i contribution to discourse on human nature and origins, no matter the exact interpretive framework you take on the subset of Baha’i scripture that deals explicitly with the philosophy of evolutionary thought.

I say philosophy specifically for a certain point. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá did not conduct scientific investigation. Although responding to the prevailing science of His time, His statements are not strictly scientific, which is to say He is not a practicing scientist despite His able vision, keen mind, and infallible role in the Baha’i community. This isn’t to deny any relevance of His statements as applied to scientific bodies of knowledge, as there is natural crossover. Rather, it is to position these as primarily rational and spiritual proofs demonstrating certain truths, from the collective body of religious and philosophical knowledge, that have a bearing on how we interpret material evidence. They are foundational arguments, and thus generative of programs of investigation in philosophical and scientific thought, but not science strictly as such. This observation is critical in two key respects:

As philosophical and religious statements, we have a primary obligation to seek recourse to philosophy and religion to weigh and consider them.

To some extent they will involve truths that are not scientifically falsifiable (which is not to say they are not verifiable or true). A corollary to this is that although one day we may with sufficient clarity affirm one or another interpretive lenses on His statements as a result of scientific advancements, they embody a core truth that is true beyond what affirmations science may hope to offer. This primacy dispels some of the tension that Donaldson attempts to accomplish through a literal resolution by recourse to scientific backing before we even get to the question of how his statements relate to scientific inquiry.

Statements such as those on evolution are relevant to the extent they overlap with scientific truths and investigation, but this is secondary, and not primarily from the perspective of scientific method or science as a body of knowledge.

The relevance and degree of overlap is subject to significant debate not only due to varying scientific frameworks and natural differences in scientific approaches and interpretation, but also because it proceeds from their clarity in their primary domain as philosophical statements. This means even the same set of scientific evidences will play out differently with respect to one’s foundational perspectives via theology and philosophy. This will become clearer shortly.

The inverse would be true for a primarily scientific statement.

To be clear, I do not mean to suggest a vision of science and religion as completely separate domains, neither infringing on the other. I am proceeding from an understanding of these as complementary, harmonious, overlapping, yet unique ‘systems of knowledge and practice’.

Bryan Donaldson pursues an exploration of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá’s thought mostly with respect to the second point above, seeking to consider how scientific evidence may or may not validate the overt import of certain statements in scripture; however, I think the first point about the primary obligation of weighing philosophy and religious statements overrides the strengths of his aims.

Proving Human Origins: To what end?

First and foremost of these is this: let us take for granted that his novel interpretation of the scientific evidence is correct, and human beings have a distinctive evolutionary origin compared to animalian life, and we, therefore, cannot strictly say human beings are animals. What then?

Well, not would change as one might hope.

Let me say first that I first affirm the value of it as an alternative model, because it would be fascinating if it were true, and it is worthy of investigation.

The interesting thing about attempting to prove this evolutionary alternative—that human beings emerged in their own evolutionary lineage—is that while such ideas are hotly contested between opposing camps of religionists/idealists vs materialists, and is taken to be a civilization-shaping debate of the modern era, e.g. the light of scientific rationality vs the dark of traditional superstition and myth, I don’t actually believe that the scientific evidence being proven true in favor of a separate lineage would shift this debate as much as you’d think, nor would it actually prove the presumed cherished premise (e.g. that man was created by God or that animals and humans are only then definitively proven as distinct). To illustrate the conundrum, one just needs to push the argument even further and grant that humans have a distinctive evolutionary line. Every prevailing philosophical challenge would remain, just at a new locus of the problem of resolving our ultimate origins. It would merely grant a certain mechanism to what is ultimately a matter not reducible to mechanism anyway. While perhaps some may be more convinced if this version of our origin were true, materialist thought could continue unabated just fine, and still consider humans as more akin to animals, as material beings, and deny the prerogatives of the spiritual should they so wish. That’s because the root of the matter still lies in metaphysical and philosophical resolutions of the question of ultimate origins, whether we are talking about evolutionary start points, the genesis of organic life itself, or the most minute components of reality.

The stakes may be large, but maybe not as impactful as one might think. The example Donaldson gives to signpost an example of how his alternative, rooted in religious text, may be legitimate after all, is that of the Quran and heliocentrism, and actually demonstrates this quite well. Islamic scholars had for centuries renegotiated signs in the Quran that can be taken in favor of heliocentrism and instead continued in the tradition of the then dominant model of geocentrism. Later, we validated that actually the Text was correct all along and found we need'nt have done that renegotiation. But has this truly advanced Quranic proofs in the eyes of skeptics? Has it proliferated the Word of God in any grand sense or served it beyond serving as a note of interest or inspiration for a subset who’ve found it confirming? Were the centuries of believers laboring under the false alternative of geocentrism diminished in their Faith as a result? I think the answer to these is actually no. The benefit for this discussion is that we can take this paradigm shift as being an example similar in scope to this question of human origins, and if our answer to these questions is no, what might it tell us about the answer for the question about human origins?

In such a hypothetical where our distinctive origin is maintained scientifically, it remains possible that one could consider humans as having emerged on a unique evolutionary tree and still consider them not to have been ‘created’ by God, nor as being more than physical. We are still discussing a fundamentally physical process which does not resolve questions that are definitively not merely physical. Indeed, the very fact that such a claim could be proven through science de facto testifies that it has remained in the realm of the material ontology. So, if this did emerge as a theory around which evolutionary science consolidated, it does not 'answer' the question of whether humans were 'created'. To suggest so would be to make a categorical error, suggesting that science can prove matters not amenable to scientific proof. Certainly it would offer many new substantive material facts to think about, but I suggest it is actually only one among many stepping stones between such major conclusions about the universe and our place in it.

Why point this out? For cooler heads to prevail in our understanding of the world, resetting our perception of the stakes can facilitate more sober analysis and free us from constrictions. If we are able to defang the intense debate between materialists and idealists, we can better weigh the evidence and admit when it leans towards one direction or another, rather than graft on questions that were never going to be fully answered no matter how the science shakes up. In fact, to invest too much into one side or another of this may unwittingly reinforce the supposed conflict between science and religion, while avoiding attending to the philosophical-theological basis of our understanding that otherwise gets neglected.

In sum: (1) I consider that we already have sufficient philosophical and religious knowledge (actualized or available to us) to demonstrate that human beings are essentially distinct from the animal which is the more important matter to beging with; (2) the domineering urge to overemphasize physical mechanism admits an untenable misconception of scientific and religious knowledge.

On this first point. Many of these same stepping stones in this grand journey self-discovery concerning humanity and our origins are ones we already have recourse to philosophy and religion to answer. Key among these is that on purely philosophical and theological grounds we already have sufficient reason to consider the essence of human being, the intellect or ‘rational soul’, as something purely immaterial, and thus not to be demonstrated in a mechanistic process anyway.

I will say in favor of strict skepticism, that I grant that scientific evidence could possibly disprove once and for all, some such philosophical-theological beliefs. Why? The demonstrable track record of falsified philosophical or religious ideas borne out of improved rational investigation is certainly impressive, and its helpful to acknowledge that possibility, as a matter of epistemic humility. There is indeed a productive dialectic at play here—a key perspective afforded by the Baha’i view on harmony of science and religion—that we will always benefit from.

But would all such beliefs fall prey?—say, for example some final, definitive evidence of the materiality of consciousness? Such a proposal that all such beliefs will inevitably fall to science is ultimately an inference that is decidedly non-scientific, and demonstrably philosophical (and probably not merited). This leads us straight back to the domain of philosophy for answers, and not strict naturalistic science, which is exactly my point. Now, let us turn to the second point, on scientific and religious knowledge.

On Scientific Revolutions & Scientific Models

Scientific Revolutions

I digress into this subject because I believe the book has admirable rhetorical and intellectual goals, however, I think it would get more mileage in these aims at this moment in scientific development through a demonstration of the philosophical validity of its exploration, rather than focusing mostly on a possible emerging evidentiary basis to the detriment of the philosophical, especially when the evidentiary basis remains too tendentious at this time comes at the expense of other justifications. The heart of the book centers on giving a fair shot at an under-explored interpretive framework: taking ʻAbdu'l-Bahá’s overtly in an effort to resolve the apparent tensions between these statements in Baha’i literature and the scientific consensus of the past century and a half. In doing so it focuses entirely on plumbing the scientific literature for some fascinating signs of progressions and interesting concepts that—assembled together and isolated from their interpretation in the dominant evolutionary model—could be viewed as movement towards an alternative synthesis of evolutionary theory. The impulse for open and inventive thinking, and pushing the needle forward within scientific thought is praiseworthy, and such reconceptualizations necessary. At their best, I argue that such efforts can counteract the stultifying influence of what Thomas Kuhn calls ‘normal science’ in his groundbreaking work, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

In Kuhn’s sociologic and philosophical observations on the nature of science, scientific revolutions are major shifts and anomalies in scientific consensus at the level of entire scientific communities that motivate novel syntheses of scientific fact in the face of crises that threaten an established consensus. The movement from geocentrism → heliocentrism can be seen as one example of this kind of shift. When enough evidence consolidates that leads to an unprecedented and new solution to an emergent problem, scientific activity then reconsolidates around this new paradigm to justify its validity and undertake to prove its success. Eventually, as such a paradigm matures, a type of scientific activity sets in that Kuhn calls ‘normal science’. This is that kind of regular scientific activity in pursuit of providing general evidence around an established scientific paradigm; but despite the original revolutionary impetus of a new scientific paradigm, eventually, the activity of scientists within it shift to a kind of ‘puzzle-solving’ activity that takes for granted the established paradigm, rather than generating anew from first principles which led to the creative disruption in the first place. The novelty diminishes and conclusions become more dogmatic, more focused on edge cases and trivialities. The theory may become overextended, or focused on ever more specific and esoteric aspects of its implications, to the detriment of serious scientific progress. In the end, a theory or scientific paradigm as a whole will need either a major modification as it bumps into newly emergent problems. Sometimes it leads to a grand new paradigm altogether. Crucially, such changes occur on the scale of decades and centuries. These are all facets at the heart of science as a sociologic phenomenon that I consider essential for one’s understanding of science, and Kuhn is still widely inspirational for the fields of philosophy of science, science and technology studies, and in the social sciences. Sadly, the implications of these reflections are still often lacking in the natural sciences.1

The relevance of this for Donaldson’s efforts is that situating efforts contra ‘normal science’ and the dominant framework requires a robust framework to distinguish the effort from mere rejection. A more rigorous basis allows for more nuance in advocating for reconceptualizing existing evidence. Further, recognition that new paradigms don’t just emerge around new evidence, but also reconceptualize existing ways of thinking about observations already made lends credence to the radical shift in mindset required to see familiar things in a new light. I think Donaldson’s work would be more persuasive if his proposals were contextualized in greater depth in light of such understandings of the sociologic process of scientific advancement, and not just possible mechanics and new evidences. This is both for his sake, in terms of clarity of thinking and grounding within a framework, but also for readers who need the guidance to contemplate a wholesale re-envisioning. This emphasis on the sociologic foundations of science opens the door to a focus not just on empirical evidence to shift one’s conception of evolution, but on how Evolution (writ-large) as a model is also an assemblage of background metaphysical and philosophical premises. One other relevance of this is that it legitimates thinking of multiple possible models of reality that have coterminous conclusions but radically different assumptions and processing of even mostly the same data, which we will explore next.

Scientific Models

Let’s take this one step further by reflecting on some meta-perspectives on scientific models. What I refer to as ‘scientific models’ here may variously be known as conceptual models, conceptual frameworks, models of reality, or at their grandest level, akin to Kuhn’s paradigms. For now, we can suffice with the provisional definition that scientific models are: (a) tools for scientific questions, (b) they depend on a mix of testable and untestable axioms and assumptions, and (c) they are capable of generating conclusions based on prevailing sets of facts, evidences, subsidiary models, and theories.

Models may coexist with each other or be mutually exclusive. At their largest level such models represent grand syntheses more akin to Kuhn’s idea of a paradigm (such as Modern Evolutionary Synthesis or General Relativity), while in certain disciplines models may be circumscribed to more specific domains of thought (cf. the Socioecological Model in Population Health). Critically, the model itself is a conceptual or intellectual reality that maps out reality on the ground; they are not reality itself and this confusion is perilous. Conclusions are only as reasonable as the model and the data that informs it, and as fallible as the humans that craft them. As the oft-cited statistical aphorism goes, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” This helps us keep a healthy distance from the tendency in science to slip into dogmatic thinking and reject unorthodox thought, a type of thinking that can lock us into to the ‘normal science’ pattern described by Kuhn [for more on models, see here].

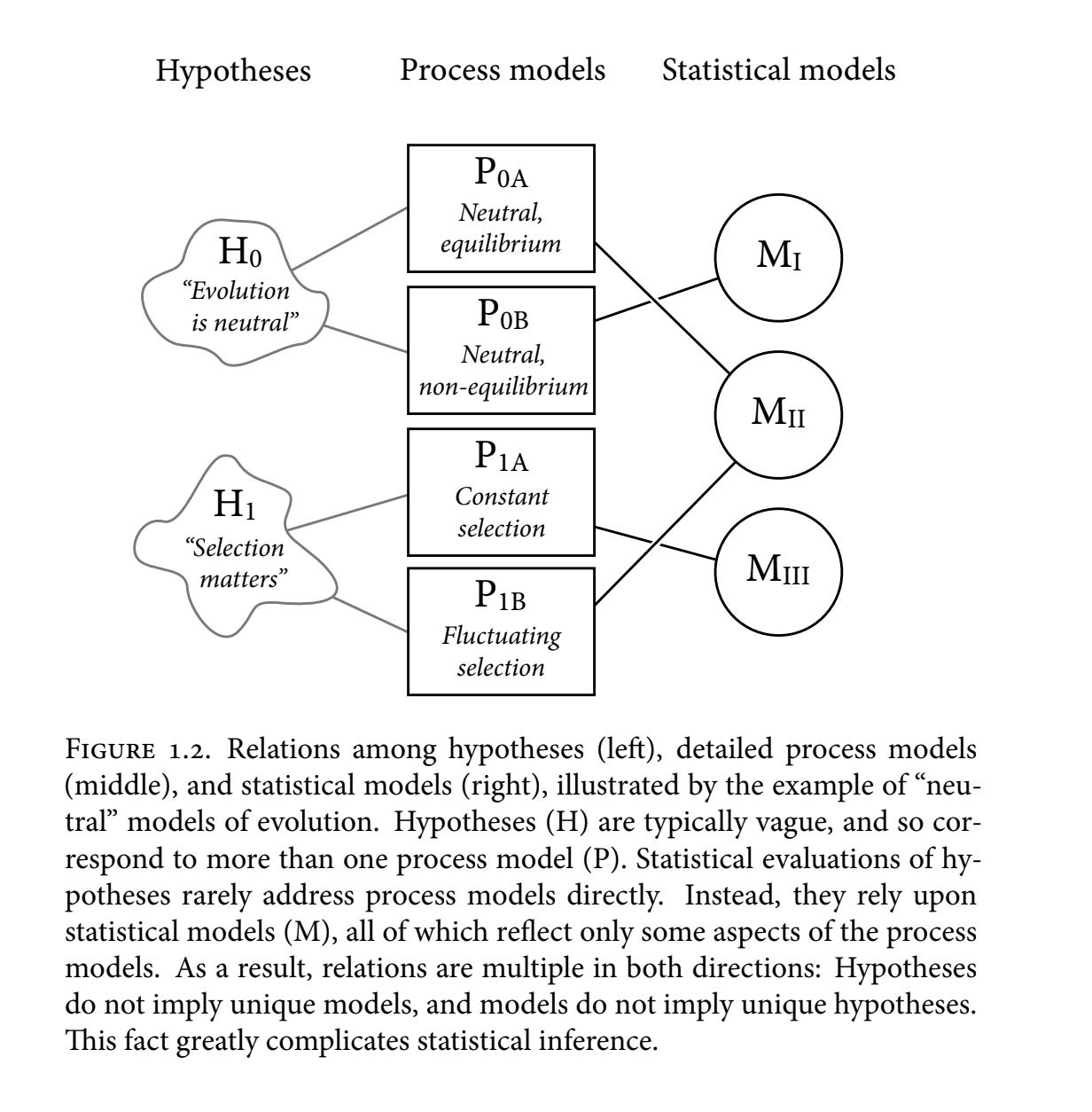

The biological anthropologist Richard McElreath, a Professor at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, offers an extremely helpful illustration of the dynamics mentioned above in his book ‘Statistical Rethinking’, alongside other important musings on how to think about scientific models.

Caption: A useful diagram that helps us think about scientific/conceptual models, from McElreath’s “Statistical Rethinking: A Bayesian Course with Examples in R and Stan”, p. 6

The above diagram is framed specifically around hypotheses → process models → statistical models, but does well to illustrate the dynamics of scientific models in their broadest scope as I am describing. It also has the added benefit of focusing on evolution. It points out that there are elements and subsidiary models within evolutionary theory that explain entire sets of observations from research, that may have their common origin in one or another distinct hypotheses. As it states, ‘hypotheses do not imply unique models, and models do not imply unique hypotheses’ and ‘this fact greatly complicates statistical inference’. I would suggest this applies to scientific inference and consensus broadly as well, and is an under-appreciated component of scientific thought. This is what I mean when I say that multiple adjacent scientific models (in the sense of Modern Evolutionary Synthesis as a “Theory” / “proven” model to explain reality) may in fact have coterminous conclusions but radically different foundational assumptions, and then also different processing of even mostly the same sets of data or subsidiary models.

I will summarize the substance of my point as follows:

Taking these factors into account can give more weight to the validity of exploring alternative syntheses; ideas such as ‘parallel evolution’ [reading this term in the context of Donaldson’s proposal] or ‘epigenetics’ that may at one time have been a laughing stock of scientific communities may, upon reconsideration, emerge as an adjacent scientific model that does powerfully explain sets of evidence and make veridical predictions to explain common phenomenon. It may even rise to the level contra the established consensus (a sign that we’d gain from adopting that model as preferable to the other). In the case of independent human origins as described in this book, whether Donaldson’s presentation justifies a displacement, or whether it really stacks up evidentially is for others to determine. A comparison at this level of model vs. model, keeping in mind these dynamics, would aid tremendously the clarity of such a determination. Ultimately my suggestion is for healthy skepticism of our skepticism, and adopting a more holistic view of scientific advancement than is usually subscribed to by those reject alternative views out of hand. Naturally those who propose alternatives must also anticipate scrutiny and be prepared for such.

Given that paradigms shift on the scale of decades and centuries, and true scientific models (on the scale of evolutionary theory) only emerge as (a) the synthesis of entire fields of endeavor, (b) intensive reconceptualization of existing bodies of evidence, (c) formulation of entirely new approaches in the field, and (d) entire communities of scientists working together, I think it is wise to weigh accordingly the efforts of one motivated thinker wishing to explore the implications of these questions in a particular direction. It is very challenging to think against the status quo, to do so with an aim to be rigorous and scientific, and advocate for a total reconception of existing frameworks. While it may not pan out or collapse under the weight of the endeavor, to the extent that we discourage such efforts (when genuine), even when they are indeed wrong, we face the unintended downstream consequence of discouraging movement towards those actual radical shifts in scientific thought that we depend on for long term progress.

General Impressions

This book is genuinely one of the more useful compilations or one-stop-shop collection of resources on the topic. It’s presented in a lucid and unassuming way—sometimes tongue in cheek and almost always accessible. Whether or not you walk away with a conclusion in support or against that of the author, you will benefit from the collection of quotes, even if you're already familiar with many of them. You will also gain from the exercise of considering the significance of the presentation of scientific concepts. The scientific evidence presented is indeed worth reviewing, and represents a smattering of interesting advancements in the field, some possible only recently, especially via technological and conceptual advancements, that offer genuine potential to reshape our understanding of human origins. One weakness of the book is that Donaldson doesn’t depict how these advancements are being conceived by those drawing on them for in favor of the consensus or in favor of less expansive revisions than his. His isn’t the only game in town. However, in reviewing this book my focus has been more on its positioning and context than the interpretation and evaluation of the scientific literature provided, which is a separate matter.

One takeaway for readers that I hope is evident is that the Baha’i approach to evolutionary allows nuance. Taken correctly, this book can help to distinguish a Baha'i understanding of evolution from the unfortunately regressive anti-science efforts of our fellow religionists from certain communities (creationism and the like) or the general impulse among many people of faith to reject scientific evidence in favor of their cherished (but untenable) beliefs. The book also demonstrates a healthy range of intellectual diversity simply by pursuing its aim with earnest, and comparing its conclusions to the existing body of literature by Baha’is, who have otherwise tended to invest more effort into contextualizing ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s statements away from denying contemporary science.

The implications of the proposal in this book are too large to ascertain in the short term. As I hope I’ve made clear, when considering sea changes in the story of scientific development, changes in the discourse of this magnitude play out on the scale of decades, sometimes centuries. We are now nearly 150 years into the ‘Darwinian era’. Is it ripe for such a disruption? The challenge is like that of the classic duck or rabbit illusion (or the modern ‘blue-black vs gold-white’ dress): the change is not always just a matter of what is added or missing in the picture, but a monumental shift in perspective in how one interprets what is present. Donaldson’s approach is to suggest such a shift in interpretation while focusing on some fascinating but inconclusive evidence proposed to motivate such a shift in the model of evolution as we have inherited it [pun intended]. Whether these changes will really amount to a generational re-envisioning, to a more modest shift that explains them via the existing model or some adaptation of it, the implications are reviewed with clarity even if ultimately one finds them inconclusive or erroneous.

To dismiss this solely as just another misguided approach by religious communities to cling to a falsified idea in their scripture would be shortsighted. This isn't a crackpot attempt to come up with an entirely different model for human origins or reject scientific thought; the author shows an able grasp of scientific thinking and mounts a genuine attempt to reckon with some an interesting possible alternative models within a scientific framework. The mere fact that it challenges the consensus AND aligns with a religious belief is often enough to dismiss outright what may be found to be challenging questions that confront the contemporary scientific paradigm. But as I suggest the philosophy of science supports, there is often more of a social component to scientific activity and interpretation than we admit. It is now genuinely not out of the question that leveraging new technologies, novel research methodologies, and more complex understandings of evolutionary possibilities that conflict with the more simple (and perhaps more simplistic?) notion of universal origin proposed by Darwin and his successors will lead to such a sea change. This doesn’t mean that Donaldson’s specific proposal will pan out, but that it would be unsurprising that a major revision or revolution will occur nonetheless. To think otherwise is to buy into a kind of dogma that undermines the value of scientific thinking itself. What that leaves us with is a pragmatic assessment of where we stand when we attempt to grasp the possibility of such a disruption when it is still perhaps glimmers on the horizon.

Some Shortcomings

A comprehensive view on the Writings

As able an exploration of the direct references to evolution in the Baha’i Writings as this book provides, the book would have benefitted from a firmer grounding in the wider totality of the Baha’i Writings. The book attempts to hone in on the specific ‘controversy’ of evolution and then seek out a possible scientific backing to explain to proposed discrepancy. Some will, on this account, dismiss this as subjecting the analysis to selection bias and motivated reasoning. I will point out that in doing so it falls victim to an all too narrow treatment of Baha’i thought, when in reality the resolution may need to be through a more comprehensive approach than analytic study the direct quotes about evolutionary philosophy alone. The quote that begins this article, “The human spirit, which distinguishes man from the animal, is the rational soul”, which obviously merits direct consideration, but is curiously missing from the analysis, is one example of what I’d expect to find but don’t. The nearest the book gets is Chapter 7, which draws from a broader range of concepts, but ends up being too thin and not integrated with the rest of the book, as a survey of the sources cited shows.

There are many other directions the exploration of Baha’i teachings could take but if you’ll indulge me I will provide one other of great importance in the at-present divergent dialogue between religion and science: teleology. Transcending a teleological cosmology or view of history has long been seen as one of the key achievements of Darwinian thought and rationalism in general. ‘Abdu’l-Baha, in the very same book as we find that core discourse on evolutionary philosophy, affirms Aristotle’s fourfold model of causality: "the existence of each and every thing depends upon four causes: the efficient cause, the material cause, the formal cause, and the final cause." (SAQ#80)2 Donaldson rightly brings out this quote in his exploration of the essence of humanness, but I’d like to dwell on it a little further to illustrate it’s relation to the core contention of the book.

Science, for it’s part, has dismissed formal causes and final causes as being outside the materialist’s purview in the course of the last few centuries of the Enlightenment. Suffice it to say we have reason to consider this a mistake. As it turns out, causation is one of the most critical topics in scientific thought and the common source of many a revolution within varying domains of scientific thought. Many fields are being reshaped in light of new conceptions of causation, even in some corners of thought, remarkably, in favor of teleology or attempting to account for purpose and consciousness-driven visions of reality. Some in the field of biology are even beginning to consider this possibility with respect to evolution. To give one precise reason why this alone would change the equation of how we conceive of evolution in Baha’i thought: the Baha’i view has already been informed by a rich depiction of the teleological purpose imbued in reality, and already affirms a critical part of the process of evolution that has everything to do with spiritual and metaphysical causation and not material. What is this you ask? The Manifestations of God. In this we already have an existing model, par excellence, that explains how humans are led to higher stages of evolution via the instrumentality of Divine Will, rather than solely driven by natural materialistic mechanisms.

The thought is this: if human beings have always been human beings, even given differences in material form, and there have always been “Manifestations” guiding us, even back into the nameless unknown time of prehistory, even pre-species, perhaps even latent in matter, then this instrument showcases the 'superstructure' of Divine Guidance leading humanity forward, ensuring the non-accidental nature of man without the need for a divergent or unique material 'base' pushing us forward. Such an instrumentality, in the Baha’i view, is perfectly capable of assuring the final cause, the telos, of the human form and its distinction in the rational soul, while allowing this to occur within the matrix of materiality, common to the animal.3 Taking this into perspective the independent or common origin of man and animal becomes of less concern. We can see this as the difference between push and pull. The two competing models posed against each other by the book attempt to explain the discrepancy solely through different 'pushing' mechanisms, while leaving behind an account for this existing clear mechanism in the Faith’s ontology of the human origins whereby humans are ‘pulled’ towards this eventuality. To this instrumentality attest the following quotes and many others:

"...the Manifestations of His Divine glory and the Daysprings of eternal holiness have been sent down from time immemorial, and been commissioned to summon mankind to the one true God." —Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings, LXXXVII

“...For every age requireth a fresh measure of the light of God. Every Divine Revelation hath been sent down in a manner that befitted the circumstances of the age in which it hath appeared.” —Bahá’u’lláh, Gleanings, XXXIV

“The holy Manifestations of God come into the world to dispel the darkness of the animal, or physical, nature of man, to purify him from his imperfections in order that his heavenly and spiritual nature may become quickened, his divine qualities awakened…” — ‘Abdu’l-Baha, The Promulgation of Universal Peace, pp. 465-466.

“Thus there have been many holy Manifestations of God. One thousand years ago, two hundred thousand years ago, one million years ago the bounty of God was flowing, the radiance of God was shining, the dominion of God was existing.” — ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Foundations of World Unity, p. 108

Here instead of the push of evolutionary forces driving humanity we see the pull of divine guidance that we are affirmed ‘has never been absent from human’ and without which we would not be human. Again, returning to the quote at the beginning of this article: “the human spirit, unless it be assisted by the spirit of faith, cannot become acquainted with the divine mysteries and the heavenly realities”. Which is to say, our humanness is dependent on (caused by) these immaterial spiritual realities for its perfection, and this is as true of the individual as it is of the collective human spirit and its emergence in time.

My point in articulating this example is to emphasize that there is far more to consider on the topic of evolution in the Baha’i thought than just the direct statements, and the over-focus on those alone can come at the expense of the holistic view. This approach runs the risk of neither clarifying and advancing our understanding on the side of the relevant theological framework, nor of servicing and demonstrating the scientific evidence in turn. This subtly reinforces the conflict the book hopes to dispel by trying to reason about Baha’i thought from a too limited domain within it (comments about evolution) at the expense of a broader synthesis (one that may satisfactorily resolve the matter altogether). I have little doubt the author is capable of and aware of those requisite broader themes, and the effort he has included is working towards this end, so I wonder if it is simply the razor-thin focus within the topic that hinders a more holistic view, leading to an overcommitment to landing on one or another ‘side’ of the seeming controversy that may be self-imposed.

Leaving supporting evidence on the table

In terms of conceptual frameworks and bodies of knowledge not from the Baha’i Faith, the book stands to have gained from incorporating broader implications and frameworks in biological anthropology and recent developments in the philosophy of evolution. Indeed, there is somewhat a fissure in traditional biological circles and anthropological circles, with bioanthropology as a field more willing to integrate robust perceptions of environmental and epigenetic intercession on the simplistic view of genetic determinism, more holistic approaches to understanding human nature, and avoid the tendency to reduce humanity to genes, genomes and physiological processes. As well as these, there is also the integration of the role of cultural evolution, and others, all of which have bearing on Donaldson’s goals. Integrating more insights from that ‘biocultural’ approach in anthropology, or their to accounting for more complex environmental effects that complicate overly deterministic views of genes and genomes; indeed there is much there that may clarify some of the proposed evidence that Donaldson review. Alongside this there are other emerging alternative frameworks in philosophy of biology & evolution that don’t always align exactly with his thesis, but a depiction of them I think would enhance the intellectual rigor of the book. Good faith articulation of alternatives—since it is not just the dominant model and his at play—strengthens the relative merit and would bring much needed clarity on how others are interpreting the evidence he presents. In all, finding more sources with common cause to reconceptualize the prevalent evolutionary model would have strengthened the book.

A programme of action

This brings me to my final point. Donaldson is not an evolutionary scientist, which he is forthright about, and this is certainly not to be held against him. I am also not an evolutionary scientist. I approach this topic from an academic training in anthropology (predominantly cultural), history, scientific training in population health, and philosophy of science. My understandings of evolutionary origins of humanity come from what I’ve gleaned through some general study of biological anthropology, mostly at the undergraduate level and certainly not from a position of authority. Others will more suitably emphasize promises or faults in the evidence, hence why my review focuses more on issues of philosophical and methological import.

I emphasize this not to dissuade any capable thinker, such as Donaldson, from the admirable goal of reviewing the evidence, posing lines of inquiry, and contributing to thought in some discipline. There is room for a whole spectrum of practitioners in any discipline, not just those doing that work ‘professionally’, and this improves science generally. I am a firm advocate of open science and scholarship.

However, the most distinctive limitation here has to do with the nature of scientific models I present above, and its not to do with lack of ability to understand the science (or even whether the interpretation is right or wrong). Rather, there simply comes a time in the work of a practical scientific field, such as biology, where one just must put into effect the research programme entailed by a certain model that you advocate for. Major advancements in science are most often measured in the span of a lifetime or decades of research, which means that in pursuit of a vision you are inspired to contribute, you may need to spend your lifetime doing so. This is all the more the case with conclusions that go against a status quo and a seeming mountain (or perhaps continent) of evidence. This occurs solely within a community of scientists oriented around pursuing a common goal to articulate a specific theoretical edifice and body of evidence towards that end. Without this, there is simply only so much ground one can cover, only so much vision one can convey, only so much buy-in you can generate in a ‘shift’, and in the end may result in merely ‘gesturing’ at potential improved models of reality and grand syntheses beyond the horizon. You also run the serious risk of being haphazard in analysis and assembling your proposals when they are not borne out in a framework of action and practice. To use an analogy from my favorite science fiction series, Frank Herbert’s Dune:

"A good hunter always climbs the highest dune before his hunt. He needs to see as far as he can see." - Jamis

*a quote from the film adaptation, Dune part 2, adapted from a quote, below, in Dune Messiah

In this case, the hard work of ascending the ‘dune’ is the process of engagement in the scientific discourse and the work of scientific activity. In replace of this there is no other suitable prism; it is not an atheoretical enterprise as some entertain, but neither can it solely be in theory. From the crest of the dune, you can take in the environs: “I see where you do not see. And, among other things, I see mountains which conceal the distances.” If you really wish to see, you must do the climb.

Conclusion

This book best services those of a Baha'i background who wish to engage with the question of the Baha'i understanding of evolution, provided that they hold it as provisional, accept it as a personal viewpoint, and inquire further into the scientific concepts it represents in its pages. While I don't think the exploration of scientific literature will be suitably thick and persuasive enough to please a thoroughly acquainted expert in biology and human origins, I do believe it is a worthwhile exploration, because it provokes questions about the relationship between science and religion that have the potential to challenge simplistic impressions. I only would have hoped that the book framed such matters more deliberately, beyond the more general discussion of science and religion it provides. On the other hand, it does keep the work more accessible.

Ideally, this book serves as a springboard to deeper contemplation on the validity of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's statements, and how they do or do not reconcile with contemporary scientific thought when taken overtly. The outcome, a more refined understanding of the spiritual foundation for Baha'i theological beliefs, will serve any Baha'i eager to advance their clarity on the topic. However, on the evidentiary and scientific side I believe the book sets up a challenge that, at best, cannot be satisfied at this time with the existing evidentiary basis. Donaldson acknowledges this, takes this challenge in stride, and tries anyway. What would need to occur is far too large a shift than the proposed alternative evidentiary basis would allow. Alternatively, the book falls under the weight of unclarified philosophical premises—the value of the search for a physiological distinction for humanity—that may actually be somewhat of a moot point, as the greater distinction has always clearly been in the spiritual distinction of reason and intellect, and the essential attributes of humanity that will remain the defining nature of humans regardless of the precise mechanism of our creation. To this testifies the bulk of the Writings and is the basis for the best arguments in favor of religious contributions on the question of human origins generally.

I am perhaps more willing than others to entertain alternative models to envision their potential to better explain existing evidence and observed phenomena; in any case I think it is worthwhile to ask yourself: if this was true, how interesting would that be? what would it mean? what does it change, what does it allow? Being willing to really see that through, even to read as if it were true (even if you know otherwise), is an invaluable skill. But one really has to weigh this with the ultimate question of the conclusions it empowers us to pursue, the axioms that accompany it, and what the attempt really has the power to shed light on, not to mention the efficacy of the evidentiary nuts and bolts it presents. In this case, I don't believe that the given conclusion resolves as many conundrums as one might hope. Although, if it were true, it could constitute one further notch towards belief rather than agnosticism, in reality I think the significance is ‘lost in the mix’ in comparison to far more compelling philosophical arguments—and more importantly noetic, gnostic, experiential knowledge, which is to say, the core of religious truth itself—that completely sidestep the necessity of independent material human origins in the first place. Nonetheless, it remains essential to undertake these investigations and we owe a debt of gratitude to Bryan Donaldson for his willingness to do the hard work of seeing how far we can take this position and proposal at the present time.

Some Further Resources

You can purchase the book here.

Since the release of Donaldson’s book, a host of newly translated talks and remarks have been released by author and translator Adib Masumian, many of which touch on the topics of humanity’s material nature, science, and the distinction of human from animal. See the book, and it’s supplement of transcribed talks.

I drafted this review after first reading the book in the months after it was released. Since then, a formal review of the book was published in the Journal of Baha’i Studies that is worth reading, and aligns with some of my impressions here, with the added benefit of being by a cell biologist, who touches on the scientific evidence presented.

The book Evolution and Baha'i Belief, by Keven Brown and Eberhard von Kitzing, remains essential.

The following presentations are worth viewing

“Evolution and the Baha'i Faith” by Steven Phelps

“Evolution and the Baha’i Faith - Redefining Humanity | part 1” by Bridging Belief

This summary broadly consults the following sources (1) ‘The Structure of Scientific Revolutions’ by Thomas Kuhn’s (2) What Is This Thing Called Science? by Alan Chalmers (3) chapters by Farzam Arbab in ‘The Lab, the Temple, and the Market: Reflections at the Intersection of Science, Religion, and Development’, (4) group discussions at a graduate seminar for Baha’i graduate students and young professionals, summer 2022

Some Answered Questions #80 (“Pre-existence and Origination”). The efficient and material causes relate to the origin and material circumstances. A hammer is contingent on an artisan or machine (its efficient cause) and is composed on materials wood and metal that are its material cause. A formal cause is the idea or form of a hammer and the final cause is the purpose for its existence (to drive nails and hit things).

There are many valences on how we can see this quintessential process unfolding, but briefly, this occurs in a robust framework and is not merely to be seen as simplistic divine intervention in material reality, but this should be saved for another discussion.

Excellent review Aaron. You are truly an independent and deep thinker.

I loved that you mentioned the involvement of the Manifestations of God over millions of years of evolution. It's something I've often thought of as a form of divine intervention in evolution, but I left it out on purpose so that the presentation would be entirely naturalistic and avoid the criticism that is heaped on creationists for emphasizing supernatural intervention.

I also agree with your descriptions of the philosophy of science and religion, and the need to avoid wrapping an air of religious truth around any scientific theory.

There is a brief mention in the introduction, pp. 7-8, that I think addresses many of your concerns, but perhaps should have been expanded upon or repeated throughout: "This book takes an untrodden approach by exploring the curent science of evolution in the context of Abdu'l-Baha's comments. Although it deals with materialistic mechanisms of evolution, it also explores the spiritual nature of human reality. Ultimately, the details of human ancestry are not nearly as important as human virtue and its place as the crowning achievement of an evolutionary process."

The book is an exploration of current science in the context of Abdu'l-Baha's comments. It is not meant to be a thesis proving a new model of evolution. Its thesis, if you can call it that, is about how Baha'is can view Abdu'l-Baha's comments, concluding on p. 220, "While it is possible to conclude that Abdu'l-Baha was speaking of spiritual potential and not material ancestry, the more apparent interpretation is of separate ancestry. I feel that it is no longer necessary to conclude that the concept of independeent or 'parallel' descent is incompatible with science. In fact, the trend of discovery has clearly been in the direction of agreement, and there are logical lines of inquiry that could entirely validate it in the next few decades."

The statements of Abdu'l-Baha are authentic and difficult to interpret in a way other than their apparent meaning. Baha'is who address this issue commonly emphasize the spiritual nature of humanity and de-emphasize or ignore source material that disagrees with their interpretation. There are really three approaches to the issue: 1) the apparent meaning is an unfortunate semantic mistake, 2) the apparent meaning is referring to something that will be validated by future scientific enquiry, or 3) Abdu'l-Baha made statements about evolution that are demonstrably untrue. For about 80 years it appears that Baha'is took the second approach, while critics took the third. The first approach avoided any association with the madness of creationist, and it was very appealing when explored for the first time in the 1990s. My emphasis was to suggest that the second approach should not be abandoned.